She and I first met at the public library in Clarkston, Georgia. Pale morning light peeked through dusty windows. Refugees, sweaty and breathless in the sticky Georgian mid-July heat, milled around the room awaiting a caseworker. A small woman, not an inch over five feet, sits down near me. The baby bump protruding from underneath her chador seems almost as big as she was. Her name is Juditte.

I finish up the details of an eviction notice with my current client when, off of the corner of my eye, I see her contort in pain and curling up. Her eyes close. Her lips part to breathe as steadily as she could.

As soon as the first client gets up, I quickly motion her over. She seems a little more stable now, but her voice is soft and scared. “I’m pregnant”, she says. “And it really, really hurts.” She has sharp pains towards the bottom of her stomach. Sometimes she bleeds more than she thinks she should.

Then, at seventeen years old, I knew nothing about pregnancy. I pull out my phone to contact a local free clinic. I tell Juditte that I’m consulting a doctor on her behalf. She panics. “No,” she gasps, her eyes wide. “You can’t. My visa is no good. I can’t go to a doctor.”

With a gentle shake of my head, I reassure her. The administration at this clinic does not check for documentation. The tension in her shoulders unravel slowly and dissipates.

I schedule an appointment with an Arabic-speaking doctor for the upcoming Monday morning and ask Juditte if she has enough food to eat at home. Is there anything else I can do for her? She declines quietly with a closed-mouth smile, breathes in deep before standing to leave the library, leaning on the shoulder of her worried husband the whole way. Refugees like her usually only stop by once; I don’t expect to hear from her again.

Ten hours later, I stare at my car windshield, after collision by a tree branch, shattered like a fragile spiderweb. Sand-like shards of glass slowly spill onto the dashboard inside. I’m parked in front of my apartment, watching the sand-shards fall and unsure how to proceed. Maybe I’m asking the universe to send me a different message.

My phone begins to ring. Unknown caller, but I pick up. I offer my mobile number incessantly — to apartment complexes, the Food Stamps office, employment agencies, and every refugee that walked into my office. Countless families await housing or food. I never miss a call.

The voice on the line comes from the free clinic I had called earlier today. She’s a doctor. Her voice maintains a controlled calm, but this unusual conversation sparks a sense of alarm in me and I can feel myself bracing for an emergency.

“I spoke with Juditte today,” she says, then pauses.

“She told me about some of her symptoms, and about how she’s bleeding pretty badly.”

Another pause.

“I think she’s having a miscarriage. She needs to go to the hospital, like now. It’s already looking bad, I don’t think she’s going to be able to survive without medical care.”

My mind raced. I moved to the Atlanta metro area not that long ago. Where did Juditte live? How could I find a hospital that would overlook a patient’s legal documentation? I didn't even know the name of a single hospital in the area.

The doctor fortunately answers one question. She names a public hospital on the opposite side of the city friendly towards undocumented immigants. Then she promptly hangs up.

Silence fills the moment. I glance at my windshield to ask, “Are you going to last the entire commute?” But I already knew my answer.

She picks up on the first ring, labored breath streaming through the phone. “Juditte?” I say, “It’s Caroline, from the IRC. We met this morning. Do you remember? The doctor just called me, and she thinks you need to go to the hospital.”

I pause... maybe I should tell her more... but her panicked “yes” tells me that she already knows. “My husband is at work,” she tells me. “There is no one to take me.”

I sweep the glass off of my dashboard and jam the key back into the ignition. “Can you give me your address? I’m on my way now.”

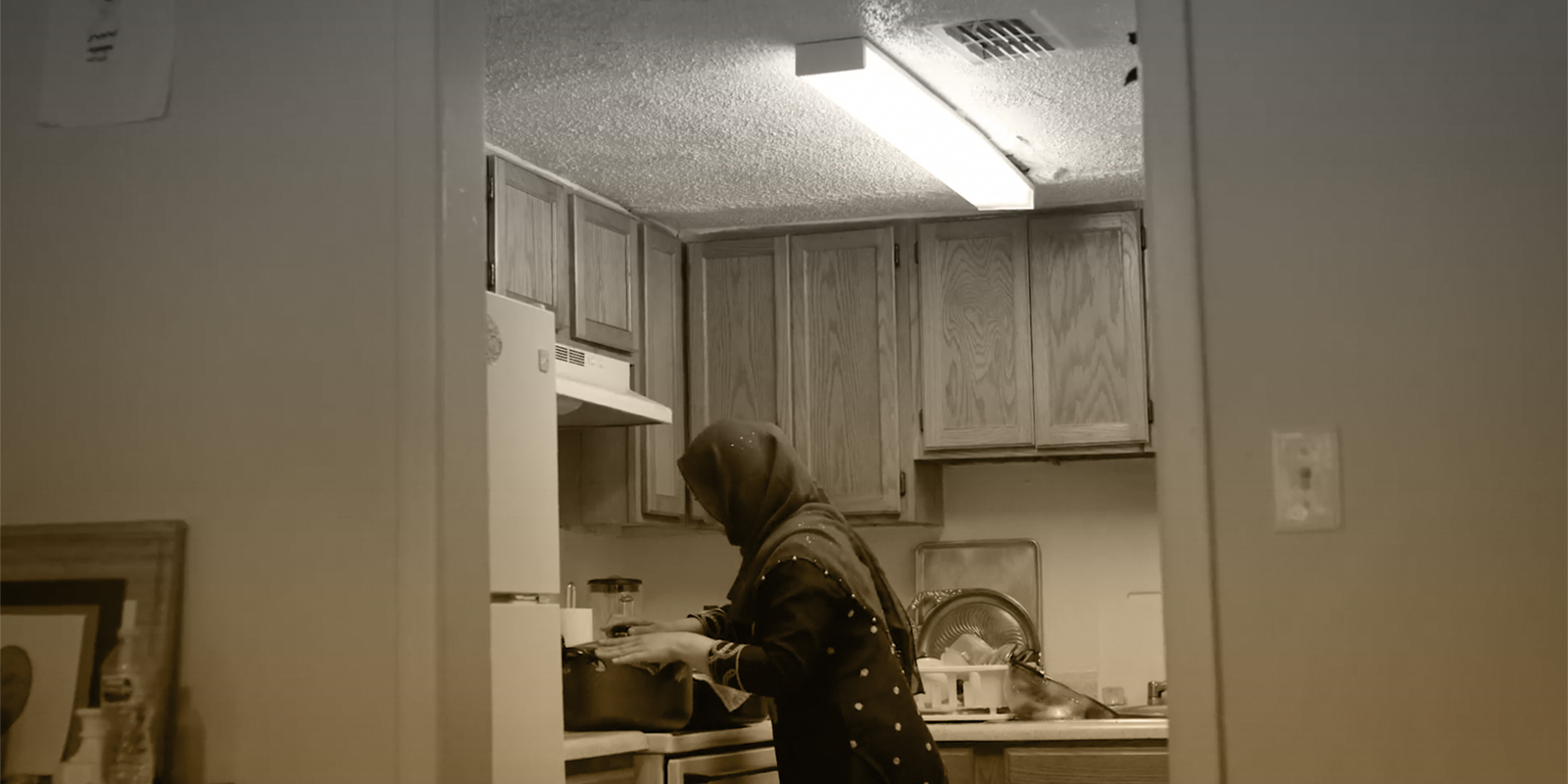

Night falls before I reach Juditte’s apartment, a home nested behind a thick grove of pine trees in the center of Clarkston and more than an hour away from the hospital. Lights flicker off as Juditte opens the door. Her face, under the streetlight, looks ashen. She leans heavily onto me as we descend the stairs together, yet by the bottom step the pain overwhelms her. She collapses onto the grass. “Go get the car,” she rasps out. “I will rest here.”

The ride to the hospital feels like two lifetimes. I drive, mentally negotiating with a windshield threatening to break apart and fly into the backseat where Juditte sits. Sprawling, she grimaces and fists towels in her hands.

We continue a distracting, meandering conversation about her best friend... about Syria where she grew up... about why she hates history but loves physics — any topic to take her attention away from the pain in her abdomen. Her voice relaxes, becoming less forced, before another stab of pain steals her breath and renders her shakily gasping for air.

We arrived at the hospital directionless. The concrete buildings without names seem to stretch on for blocks. I hastily pick a parking garage and practically carry Juditte inside, placing her on a couch before sprinting to the front desk.

“She’s having a miscarriage and bleeding badly, very badly. Where do I need to go?” The nurses are much too jubilant for my liking. They leisurely stroll over to Juditte, load her into a wheelchair, and exchange jokes among themselves on the elevator up to the fourth floor. Juditte moans faintly, wiping her hands on the side of her jacket. She has bled through her chador.

The nurse looks over at her briefly before returning to me. “Have a seat over there,” she gestures at a lime couch under a television tuned to the evening news. “We’ll be with you in just a minute.”

We sit gingerly. A young mother sitting opposite of the couch, waits for them to leave earshot before whispering, “They said that to me, too. I’ve been here for six hours.”

I bite my lip and nod, smiling at Juditte, “They’ll be with us very soon.”

Eight hours come and go before Juditte is lying on a hospital bed. She shivered uncontrollably in the waiting room, but she seems warmer now. Her eyes close. Her fingers move softly against the blankets.

Pallid hospital fluorescence blinks above me, like a visual drumroll, as the question of what will happen to Juditte and her baby hangs in the air. I’m suddenly, immeasurably, indescribably tired.

Some more time passes before the nurse walks back in. I catch her regretful eyes, and my heart sinks onto the floor. “We couldn’t find anything on the ultrasound,” she finally offers. “The baby is gone. I’m so sorry.”

Volatile emotional energy hums in the room... until Juditte relinquishes a long and soulful sigh. “Oh” is all she says. Her face remains stoic. Her brown eyes, peering wistfully at some lost future nobody else could see, are now slightly dimmer than they were before.

We leave the hospital in short fashion. Her body leans on mine again, this time from fatigue instead of pain. She sleeps on the drive to her apartment. I wonder what to say to someone who just lost their child. No words seem to be the right ones.

Through my work, innumerable faces imprint themselves in my memory. Some invoke bravery. Others appear when I think of passion. But for delicate, amber sunrises and soft, breathy voices... in moments of witnessing an undefinable love of life, I remember Juditte’s. She fought so relentlessly to try to save the life of someone she had not yet met. She loved so fiercely someone she had yet to see. Unconditional love begets pain. This is the kind of love that I aspire to give to others through my work.

I attempt to help her walk up the stairs at her apartment. She shakes her head with the same quiet strength she wielded as I met her. She smiles softly. “That’s okay,” she says. “I’ll be alright.” She climbs the last steps by herself and mouths “thank you” to me as the sun peaks over the horizon. It was the last I saw of her.